CSIRO-backed Flexi diet evidence review

Aractus

Introduction

The diet industry is huge. And mostly it doesn’t work. Why is this? Well, it’s actually quite straightforward. People are set up for failure by an industry that thrives on people failing and coming back. They don’t really care whether their clients succeed or not, so long as they can profit from their efforts. I have a huge ethical problem with this, and I think any service should be covered by a guarantee. Instead, people blame themselves for the failure of commercial weight-loss programs, and the industry doesn’t take responsibility for their failures. In this entry what we’re going to look at is the peer-review published evidence for the Flexi diet, and I’ll go over whether or not it is sufficient to guide clinical practise.

The first thing I wish to ask is – how would you define success? Is yo-yo dieting/weight-gain a success? Is short term weight loss a success? Take a moment to consider these questions, they’ll be addressed as we proceed.

What is the “Flexi diet”?

The Flexi diet is “backed by CSIRO research” (CSIRO, 2016). When I first heard about this, I thought the CSIRO had designed and published a diet in the form of a book… I think I first heard it on the radio, and the media was reporting that the CSIRO launched an intermittent fasting diet for weight loss (Connery, 2017; Powley, 2017; SBS, 2017). In fact the CSIRO website also makes this claim. In reality they “co-developed” it, but it’s questionable as to exactly what they “developed” and wish to take credit for.

Despite repeated claims of this on the Impromy website they do not provide the citation to the paper itself. Even more bizarrely, neither do the CSIRO on most of their pages on Flexi including their blog announcement! I’ll refer to the research paper as the “CSIRO paper”, here is the paper’s citation,with a link to it so you can read in full if you want:

Brindal, E., Hendrie, G. A., Taylor, P., Freyne, J., & Noakes, M. (2016). Cohort analysis of a 24-week randomized controlled trial to assess the efficacy of a novel, partial meal replacement program targeting weight loss and risk factor reduction in overweight/obese adults. Nutrients, 8(5), 265. doi:10.3390/nu8050265

In a nutshell, the Flexi diet is a ~30% energy deficient diet that uses commercial meal replacement (MR) shakes and one high-protein meal six days a week. One day a week is a free day. The so-called “fasting days” are simply further energy restricted compared to the other energy restricted days. A more detailed description of the diet is in the following sections.

Description of the study

The study took place over a period of 24 weeks, and predominantly considered whether a program incorporating commercial meal replacement shakes, controlled diet, iPhone app, and ongoing dietary support would support weight loss for participants. In other words they studied a proposed commercial product, which eventually became known as the Flexi diet by Impromy.

The paper begins by informing the reader that lab data and real-world data are often very different, citing that meal replacement and other weight management strategies have been promising in trials, but that their efficiency in the real-world drops significantly. As noted in the paper, in just about all programs available through pharmacies weight-loss become negligible after the first 12 months. These issues will be discussed later in this essay.

The CSIRO study involved observing two intervention groups. All their participants were randomly assigned to one of two intervention groups, with both receiving the same intervention with the exception that one group was given a more basic iPhone app than the other. There was no control group. The study environment was a CSIRO lab and not a pharmacy. In total there were 146 participants, 104 females and 42 males. 27 participants were overweight, the remainder were obese (BMI 30+). The intervention period was 24 weeks, with 12 weeks of “active intervention”. “Active intervention” involved face-to-face meetings with non-nutrition trained consultants who had been given program-specific training from dieticians involved in designing the program. Participant-reported data was relied on primarily for care, and their weight was measured regularly by the consultants. They were also asked to provide feedback on their satisfaction of the meal replacement shakes throughout the program, as well as questions from the consultants that included “what has been the most helpful aspect of the program” (which was asked in week 12). Many of the feedback questions were targeted towards improving the prototype program rather than studying the program objectively per se. Meal replacement sachets were free for the first 4 weeks, and then provided at a nominal cost of $1 each for the remainder of the study.

The findings of the study were modest. 84 participants (58%) completed the study. Of those who completed, 72 offered 94 comments on the meal replacement shake, of those 57 were identified as positive comments, and 16 as negative. 33.5% of all participants lost weight over the study period. All significant weight loss occurred by week 12, with no significant change in weight between weeks 12 and 24.

The CSIRO paper cites Gordon et al. (2011) a systematic literature review which found that pharmacy based weight-loss intervention programs only achieve modest results. The Gordon paper found such methods only achieved an average weight-loss of 0.6-5.3 kg in the first 3 months, 0.5-5.6 in the first 6 months, and just 1.1-4.1 kg over the first 12 months. It’s important to mention to you the design of their study as it is not addressed in the CSIRO paper: this is not a review of all pharmacy weight loss products, rather it is a review of peer-review published “studies” of such products. Only 10 studies met inclusion criteria for a systematic review, and the paper’s authors report that this likely represents a strong bias towards meaningful results. That is many other programs that were available were either: not studied at all, studies undertaken went unpublished, published studies did not meet the inclusion criteria (eg did not take place in a pharmacy setting was the main reason for published papers not being included), or the focus of the study wasn’t weight loss. All 10 of the studies included were multi-factor interventions that included dietary and physical activity components. Finally, the authors noted there was a strong risk of bias in all of the studies which the CSIRO does not mention in its citation of this paper.

Discussion

The paper’s premise that pharmacy-delivered weight loss intervention programs are advantageous, is highly questionable to say the least. Any positive findings from the cited Gordon paper are not relevant to this study for several reasons including that: all trials reviewed in it included a physical activity component, and all trials were conducted in actual pharmacies and not research labs. Literature consistently shows that interventions that combine diet and exercise provide patients greater weight loss (Franz et al., 2007; Johns et al., 2014). Furthermore it represents but a small fraction of the weight management programs available in pharmacies, many of which are quackery! The Gordon paper is their best evidence from the literature for delivering weight-loss programs through the pharmacy, yet read below what the paper actually says in its conclusion:

“This systematic review identified few high-quality studies on weight management in community pharmacy. Currently, there is insufficient evidence for the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of community pharmacy-based weight management initiatives to support investment in their provision.” (Gordon et al., 2011).

CSIRO authors correctly point out that successful lab studies generally provide participants with ongoing multidisciplinary professional support at no cost for the duration of their clinical trials. This should not surprise us! In fact, it completely discredits their hypothesis that any commercial program will succeed. Finding effective low-cost long-term solutions continues to be evasive. People who wish to lose weight will be far more successful by working directly with a dietician or a registered nutritionist on a tailored program: no commercial program has been shown to even approach an equal degree of success. In fact, most of the commercial programs are not designed and targeted for people who are obese, but rather people who are only slightly overweight. Cost is a big factor: clinical trials as mentioned are generally free to participate in. Commercial programs are expensive and need to fit into people’s budgets. Working directly with a registered nutritionist or a dietician is also expensive, however they can provide their clients suitable and realistic diet plans instead of generic plans produced for mass-consumption that don’t fit most overweight or obese clients. This begs the question: why is the premise of the CSIRO study to deliver a program through pharmacies instead of through dieticians?

Some of the claims in the paper are dubious to say the least:

“For longer term success on a program such as this, providing individuals with the flexibility to transition through to fewer meal replacements as their weight loss progresses or as fatigue with the shakes sets in becomes an important element for success. Pharmacy staff are ideally placed to assist the community with weight loss as they are readily accessible and can be available to consultant with individual’s on an as needs basis, potentially quicker that seeking advice from other health professionals. However, appropriate training and tools are required to ensure pharmacy staff delivering the program (not qualified in nutrition) have adequate support to facilitate such a transition through a weight loss program.” (Brindal et al., 2016)

These findings in particular are concerning as they did not recruit pharmacy staff. Nor did they do any research into determining whether people would actually approach pharmacists for dietary advice and assistance with weight management. Nor did they attempt to find out if this is something pharmacists would do instead of say directing a client to a registered nutritionist. Why should pharmacists who are health professionals administer a commercial weight loss program that is not supported by evidence? Even Impromy’s own forum shows the flaw in this logic: “Just opened up the program. … I’m thinking this appears to be more a money making venture, rather than a supported diet. … The Pharmacy wasn’t much help at all.” (C. Kendall, Impromy discussion forum). The last question from that participant on the online forum has gone unanswered for two straight weeks! I don’t imagine the pharmacy will help either – is this really the realistic supportive environment envisioned in the study?

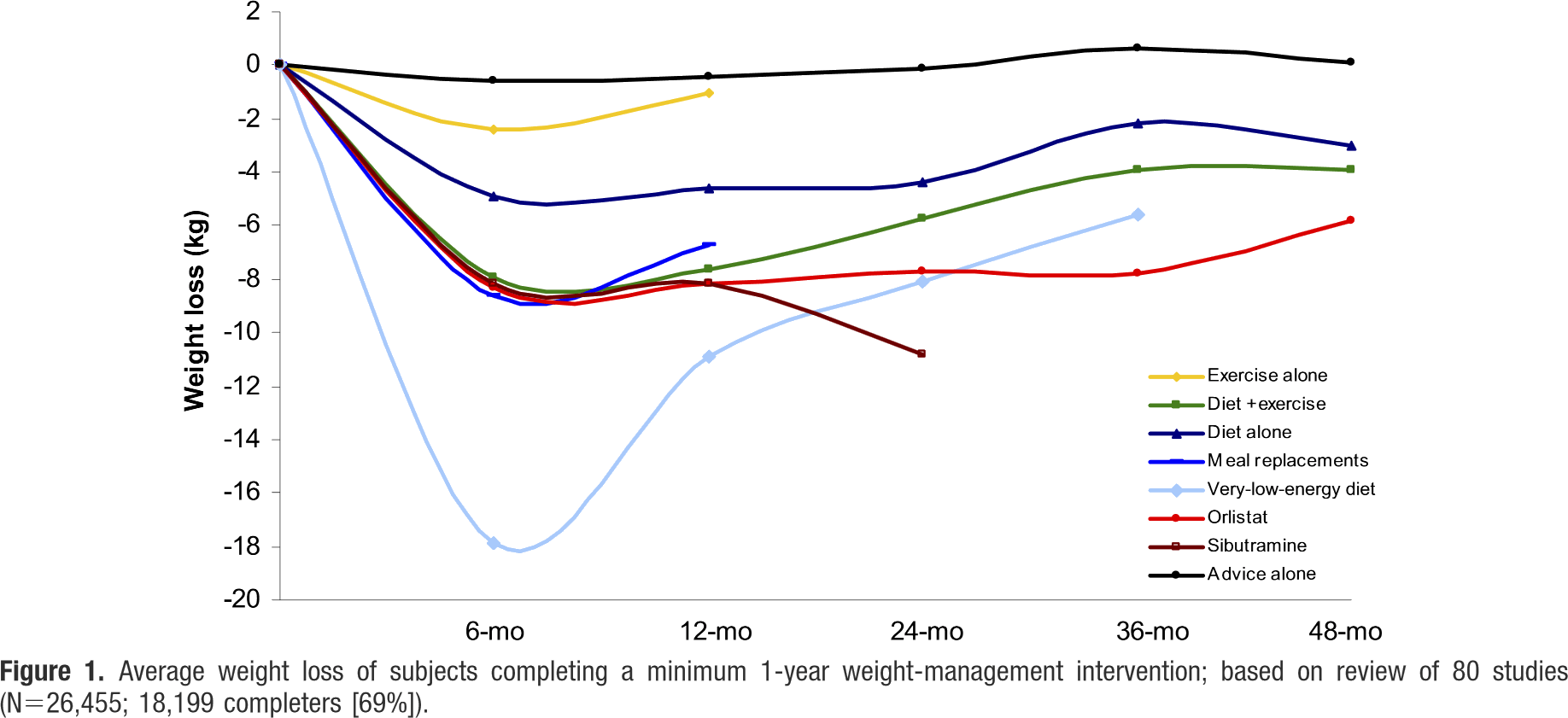

I’m going to show you something the diet industry doesn’t want you to see:

Figure: Franz et al. 2007.

The figure is from a high quality literature review. As you can see, none of these interventions can be shown to work long-term except for maintaining some of the weight loss experienced in the first 3-6 months. The only thing in that review that kept going was an appetite suppressant (Sibutramine) that’s since been banned by the TGA (also the FDA in the US) in 2010 due to serious adverse side effects. This is why the diet industry is so big – nothing works long-term. Weight-loss doesn’t continue beyond 6 months. Only half the weight lost is maintained to two years, and often all the weight is regained over 5 years. I guess that’s fine if you just want to lose 8kg in 6 months and don’t mind putting back on 4kg. But – keep in mind that most participants at least in this study are obese. A person who is 5′ and slightly obese needs to loose a minimum of 12kg to get to a healthy weight. A person who is 6′ needs to lose 18kg. And have you ever noticed how there are dozens of “12 week” weight-loss products? Now you know why. It’s not because they’re great products, it’s because people won’t notice they don’t work if they stop after 12 weeks!

There are several problems with the CSIRO study. Firstly it’s far too small to generalise data from, and it doesn’t have any follow-up data after six months. There was no control group – therefore this is not an RCT but just an observational study. It’s not in the commercial interests of Impromy to commission an RCT (randomised control trial) as it would likely show their intervention to be ineffective as is the case with the Ahrens paper reviewed by Gordon et al 2011 (and the only RCT in their review). An academic description of it reveals there was no statistically significant difference in the weight loss outcomes compared to the control group that were given a traditional energy-restricted diet (Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2006). The CSIRO study environment was not a pharmacy, and the trial was not delivered by pharmacists. Participant-reported data was relied on, when we know that is problematic. And the “satisfaction feedback” is unlikely to have produced meaningful feedback: people participating in studies are often willing to say more positive things about their experience then real-world clients or customers would.

Conclusions

Overall this is a low quality study that is not suitable to guide clinical practise. And that’s putting it as nicely as I can. As mentioned there are many problems with this study, it is low quality by design. It’s not really designed to find best practise, it’s just designed to produce a result. They lack a control group which is absolutely necessary to make any clinical guidelines from. There is no doubt at all that expecting participants to get ongoing support from pharmacies is wholly unrealistic.

The program produces mediocre results. Some media incorrectly reported that participants lost an average of 11kg (I have no idea why, perhaps they extrapolated the finds from 24 weeks to 12 months or something), but in reality the amount of weight lost was nothing special and well below the amount required to make the participants healthy. In other words, they’re selling a diet that fails to achieve a healthy weight even for participants that were only slightly obese. A successful program should at the very least reduce the weight of obese category one clients (BMI 30-35) to a healthy weight. There is no suggestion in the paper that any of their 117 obese clients achieved a healthy weight. Which is not surprising of course in only a 24-week period, but nor is there any indication that their clients were on track to do so: in fact the paper states that weight-loss ceased after the first 12 weeks!

The CSIRO are doing themselves no favours by promoting this “weight-loss diet”.

Recommendations

What should you do if you wish to lose weight? My suggested starting point is to learn the Consumer Healthy Eating Guidelines (that’s the AGTHE in Australia, MyPlate in the US, etc). Those guidelines are freely available and evidence-based, and you can read the literature behind them. Unfortunately most consumers ignore them. If you’re OK with a more restrictive diet you can also consider using DASH or the Mediterranean diet guidelines. None of those are weight-loss diets of course, but they are all health-promoting and provide a solid foundation for learning portion sizes and the right balance between the food groups. Meal replacement diets suffer the problem that they don’t re-educate people into healthy eating, and people often find themselves lost when working out how to eat once the MRs are gone.

A good starting point would be elimination of “discretionary foods”, and a strong focus on eating enough fresh fruit and vegetables (most people don’t eat enough veggies). If you can work that out, then weight-loss is as simple as creating a moderate energy deficiency with of course a long-term commitment to substantially altering one’s lifestyle.

Physical activity also needs to play an important role. When it comes to this there are many options available to people – sports, gyms, swimming, cycling, jogging, walking, altering the workplace environment, dancing, martial arts classes, etc. People should seek solutions that work for them.

References:

(Academic)

Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2006. AWM: Meal Replacements (2006). Evidence Analysis Library (if page doesn’t load clear cookies)

Brindal, E., Hendrie, G. A., Taylor, P., Freyne, J., & Noakes, M. (2016). Cohort analysis of a 24-week randomized controlled trial to assess the efficacy of a novel, partial meal replacement program targeting weight loss and risk factor reduction in overweight/obese adults. Nutrients, 8(5), 265. doi:10.3390/nu8050265

Franz, M. J., VanWormer, J. J., Crain, A. L., Boucher, J. L., Histon, T., Caplan, W., … & Pronk, N. P. (2007). Weight-loss outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of weight-loss clinical trials with a minimum 1-year follow-up. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 107(10), 1755-1767. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2007.07.017

Gordon, J., Watson, M., & Avenell, A. (2011). Lightening the load? A systematic review of community pharmacy‐based weight management interventions. Obesity reviews, 12(11), 897-911. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00913.x

Johns, D. J., Hartmann-Boyce, J., Jebb, S. A., Aveyard, P., & Group, B. W. M. R. (2014). Diet or exercise interventions vs combined behavioral weight management programs: a systematic review and meta-analysis of direct comparisons. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 114(10), 1557-1568. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2014.07.005

(Non-Academic)

Connery, G. (2017). CSIRO backs fasting and meal replacement shakes in new ‘Flexi’ Diet. Fairfax News

CSIRO. (2016). Impromy™ Health and Weight Management Program. CSIRO website

Powley, K. (2017). How does the CSIRO’s new flexi diet rate? News Corp (subscription) / Mirror

SBS. (2017). Researchers examine time-restricted eating. SBS News

Tufvesson, A. (2012). The CSIRO’s Flexi diet weighs in as the fast way to avoid fasting. The New Daily

1